The Story of the Silos, As Told Through Explosions |

After you took me to the silos for the first time, I knew I’d be back. With other abandoned sites, there was this interim thrill, knowing cranes would render it to dust the minute you left. Most places I go are temporary; you visit to ride the crest of the wave before it crashes. With the silos, no one is afraid of them really going anywhere. After all, they’ve been around longer than Willis Tower or Wrigley Field. They’ve suffered countless explosions. The city around them collapses and falls, but the silos stand still. A point of convergence in a world of chaos.

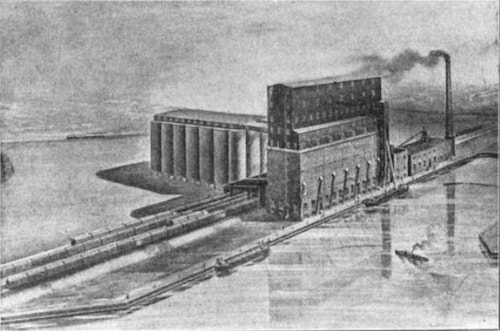

It is September 9, 1905. A spontaneous combustion roars on the bank of the Chicago River. Nearly a million bushels of grain erupt in flames. It’s like a Michael Bay movie, but he won’t be here for another hundred and ten years. The Santa Fe Railroad stores its cargo in this facility, a riverside grain elevator that’s been around since the early 1800s. Within an hour, it’s gone. This is the second time it’s happened. Someone needs to build something that can last for more than thirty years without catching on fire.

Instead, someone builds something that will outlive the grain industry itself, despite constantly catching on fire.

Instead, someone builds something that will outlive the grain industry itself, despite constantly catching on fire.

It is 1906. The Cubs have just lost the World Series to the White Sox. 75% of San Francisco is destroyed in an earthquake, but new railroads are rambling west anyway. Chicago is on its way to leading the nation in grain production. Amidst the chaos, John Metcalf is designing the set of Transformers for the Metra.

Back at this point, there are no Transformers. Michael Bay’s grandmother is a toddler. The Metra is painted bright red, travels at 60 miles per hour, and is called the Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad (despite accessing virtually every big city except Santa Fe). Metcalf is actually tasked with making a grain elevator off the bank of the Chicago River, what will soon become the site’s first recognizable form in a series of unforgiving reincarnations. He has no way of knowing he’ll make the same mistake as every other man building a grain elevator, sending the cement monstrosity into its tween years as a spray-paint-and-broken-windows emo phase.

Instead, the elevator is finished. It is ceremoniously named the Santa Fe Railroad Grain Elevator, but most people probably know it as That Giant Eyesore on the South Branch. This is a time before tufts of skyscrapers stubble Lake Michigan’s coast, a time when such a cement monstrosity rises from rubble like an 80-foot industrial-era fist. Imagine, a skyline with only one building! A train with only one purpose! A future with only one possibility!

It doesn’t happen. The grain silos don’t bring the railroad to an age of prosperity and fame. Instead, they keep accidentally blowing themselves up. Of course some people are upset, but apparently this happens all the time. Tons of grain elevators meet this same demise, especially in Chicago. It’s something about the way the dust mixes with oxygen. No one understands it. We live in a cruel world.

Back at this point, there are no Transformers. Michael Bay’s grandmother is a toddler. The Metra is painted bright red, travels at 60 miles per hour, and is called the Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad (despite accessing virtually every big city except Santa Fe). Metcalf is actually tasked with making a grain elevator off the bank of the Chicago River, what will soon become the site’s first recognizable form in a series of unforgiving reincarnations. He has no way of knowing he’ll make the same mistake as every other man building a grain elevator, sending the cement monstrosity into its tween years as a spray-paint-and-broken-windows emo phase.

Instead, the elevator is finished. It is ceremoniously named the Santa Fe Railroad Grain Elevator, but most people probably know it as That Giant Eyesore on the South Branch. This is a time before tufts of skyscrapers stubble Lake Michigan’s coast, a time when such a cement monstrosity rises from rubble like an 80-foot industrial-era fist. Imagine, a skyline with only one building! A train with only one purpose! A future with only one possibility!

It doesn’t happen. The grain silos don’t bring the railroad to an age of prosperity and fame. Instead, they keep accidentally blowing themselves up. Of course some people are upset, but apparently this happens all the time. Tons of grain elevators meet this same demise, especially in Chicago. It’s something about the way the dust mixes with oxygen. No one understands it. We live in a cruel world.

It’s 1932. The third explosion hits. Since it’s the peak of Chicago’s gold-hued grain reign, the site is rebuilt and expanded to hold twice as many bushels. It operates for 45 more years before self-destructing in another accidental explosion. By 1977, grain isn’t profitable enough for anyone to bother fixing it. After almost a century of sifting, Damen settles into a brief retirement. The Cubs lose the World Series again, this time to the Yankees.

Unsafe for operation, the 35 silos sit on the river bank in varying stages of decay. The Department of Central Management fails to sell the property, since the buildings have to be completely demolished before they can be remade into anything workable. To some, it’s still an eyesore, especially as it accumulates graffiti and grime. But in Chicago’s undemolished trash is Hollywood’s treasure. Michael Bay arrives at the site, determined to turn the riverbank ruins into a movie set. The crew wipes off the skulls and swear words, then replaces them with giant Mandarin characters. For the first time in 35 years, the Damen Silos are alive again. Maybe all they needed was more explosions.

Unsafe for operation, the 35 silos sit on the river bank in varying stages of decay. The Department of Central Management fails to sell the property, since the buildings have to be completely demolished before they can be remade into anything workable. To some, it’s still an eyesore, especially as it accumulates graffiti and grime. But in Chicago’s undemolished trash is Hollywood’s treasure. Michael Bay arrives at the site, determined to turn the riverbank ruins into a movie set. The crew wipes off the skulls and swear words, then replaces them with giant Mandarin characters. For the first time in 35 years, the Damen Silos are alive again. Maybe all they needed was more explosions.

It’s 2013. Transformers: Age of Extinction comes out and makes so much money that some people think it’s actually good. Anyone watching the movie assumes the Damen Silos are in China, which just goes to show that they were more talented at acting than the rest of the cast.

At this point, the Damen Silos have breezed from industrial grain grinders to hollywood actors, but despite the impressive resume, no one’s buying. The price drops to almost 500% to $3.8 million while the Department of Central Management attempts to sell the place off, one last time. It’s a good deal, they advertise. It’s the last plot of open land available in the city. Nobody seems to care.

At this point, the Damen Silos have breezed from industrial grain grinders to hollywood actors, but despite the impressive resume, no one’s buying. The price drops to almost 500% to $3.8 million while the Department of Central Management attempts to sell the place off, one last time. It’s a good deal, they advertise. It’s the last plot of open land available in the city. Nobody seems to care.

It’s 2017. Taylor Swift’s new album is crooning on the radio. For once, the Cubs win the World Series. It’s a warm night for December.

Our Uber driver Margarite pulls to the side of the road. We direct her to stop right before the neon signs. On another night, in another car, the driver would have asked what two young kids were doing at this off-the-path business park at eleven o’clock on a Saturday night. Margarite isn’t like that, though, and she kills the engine. We thank her and start walking.

You hold the fence open for me so I can crawl under. We cut through a field of reeds, picking our way toward the first structure. I have no idea what happened in this building, but as I trace the crumbling metal framework with a dusty finger, I imagine it was once a warehouse of sorts. There was a place like this in my hometown, with the same cavernous interior and grimy corners. Boys used to sneak off there so they could make out with their girlfriends.

We find a staircase that crumbles and curves in such a demonic pinnacle that you know you have to climb it just because every mother in the world would tell you not to. We leap to the roof, tip-toe across the metal beams because they’re sturdier than what remains of the tar. We take pictures with the graffiti at our backs.

I’m looking for a window to stand in when I accidentally catch sight of the city. From here, only a few minutes’ walk from the Ashland Orange Line, Chicago is dim. It looks like it could almost be a collection of close-knit stars. When I try to take a picture with my phone, I end up with grainy purple darkness. It’s the worst photo I’ve ever taken, but I’ve caught the universe in my hand.

Our Uber driver Margarite pulls to the side of the road. We direct her to stop right before the neon signs. On another night, in another car, the driver would have asked what two young kids were doing at this off-the-path business park at eleven o’clock on a Saturday night. Margarite isn’t like that, though, and she kills the engine. We thank her and start walking.

You hold the fence open for me so I can crawl under. We cut through a field of reeds, picking our way toward the first structure. I have no idea what happened in this building, but as I trace the crumbling metal framework with a dusty finger, I imagine it was once a warehouse of sorts. There was a place like this in my hometown, with the same cavernous interior and grimy corners. Boys used to sneak off there so they could make out with their girlfriends.

We find a staircase that crumbles and curves in such a demonic pinnacle that you know you have to climb it just because every mother in the world would tell you not to. We leap to the roof, tip-toe across the metal beams because they’re sturdier than what remains of the tar. We take pictures with the graffiti at our backs.

I’m looking for a window to stand in when I accidentally catch sight of the city. From here, only a few minutes’ walk from the Ashland Orange Line, Chicago is dim. It looks like it could almost be a collection of close-knit stars. When I try to take a picture with my phone, I end up with grainy purple darkness. It’s the worst photo I’ve ever taken, but I’ve caught the universe in my hand.

You tell me we’ve got to see the other building, so I tuck my hands back in my pockets and sail down the sorry excuse for stairs. We’re quiet as we cross back through the reeds. The world around us is, too. This is the least noise I’ve ever heard so close to Chicago. The calm before the storm.

There’s a security guard that doesn’t catch us when we cross over into the silos. You show me how to find the window and make my way inside. I don’t wait for you before wandering into the basement, winding my way through the halls, stopping before a huge pit of sand. Dust motes flirt in front of my eyes and I flinch like they’re after me. Looking down, my shoes have disappeared up to the ankles. There’s an odd chill that tickles my skin, more like the canned breath of a refrigerator than the kinetic flush of a breeze. I imagine this is what it would feel like to be on the moon. You ask me where we are.

To be honest, I don’t know. I’ll never know. In fact, despite amassing a detailed history I know by heart, I’ll always step inside the Damen Silos without the slightest idea how they were used. What used to fill this space? Bushels of grain? A man with a clipboard? Michael Bay and Mark Wahlberg? Perhaps, this was the site of one of those many explosions. Maybe, my boots sift through what remains of the aftermath. Or maybe, it’s just sand.

We stay for a long time, but green flashing lights let us know that the security guard is making rounds. We take the opportunity to leave, finding our way to the same hole in the fence that we used as our entry. It’s still a warm night, so we walk to the L stop to shake the sand from our shoes. We’re the only ones on the platform after we swipe in. It’s not a frequently-visited part of town, so there isn’t another train coming for twenty-eight minutes.

There’s a security guard that doesn’t catch us when we cross over into the silos. You show me how to find the window and make my way inside. I don’t wait for you before wandering into the basement, winding my way through the halls, stopping before a huge pit of sand. Dust motes flirt in front of my eyes and I flinch like they’re after me. Looking down, my shoes have disappeared up to the ankles. There’s an odd chill that tickles my skin, more like the canned breath of a refrigerator than the kinetic flush of a breeze. I imagine this is what it would feel like to be on the moon. You ask me where we are.

To be honest, I don’t know. I’ll never know. In fact, despite amassing a detailed history I know by heart, I’ll always step inside the Damen Silos without the slightest idea how they were used. What used to fill this space? Bushels of grain? A man with a clipboard? Michael Bay and Mark Wahlberg? Perhaps, this was the site of one of those many explosions. Maybe, my boots sift through what remains of the aftermath. Or maybe, it’s just sand.

We stay for a long time, but green flashing lights let us know that the security guard is making rounds. We take the opportunity to leave, finding our way to the same hole in the fence that we used as our entry. It’s still a warm night, so we walk to the L stop to shake the sand from our shoes. We’re the only ones on the platform after we swipe in. It’s not a frequently-visited part of town, so there isn’t another train coming for twenty-eight minutes.

It’s 2017. Still no one wants to buy the Damen Silos. They belong to no one, but in another sense, they belong to everyone. I remember looking out across the river, squinting to make out the lines of the city, sifting through sand with the mottled toe of my boots. They belong to me, I think. Don’t take them away.

This year, there isn’t an explosion. Grain is stored in fireproof containers now. Michael Bay is making a documentary on poaching elephants. They’re up to the seventh Transformers movie. The BNSF doesn’t run this way anymore, and everyone calls it the Metra. The industrial world was born and replaced with something faster and less flammable. This place has become a relic.

We’re on our way home when I tell you it’s more than just an adult playground. This place has been through film, factory, and flame. At one point, there were fifteen floors that held 800,000 bushels of grain.

Now, the stories are all that’s left.

This year, there isn’t an explosion. Grain is stored in fireproof containers now. Michael Bay is making a documentary on poaching elephants. They’re up to the seventh Transformers movie. The BNSF doesn’t run this way anymore, and everyone calls it the Metra. The industrial world was born and replaced with something faster and less flammable. This place has become a relic.

We’re on our way home when I tell you it’s more than just an adult playground. This place has been through film, factory, and flame. At one point, there were fifteen floors that held 800,000 bushels of grain.

Now, the stories are all that’s left.

VANDALS originally published for North by Northwestern, 10/25/2016 |

Caitlin twisted a thimble-sized plastic cap between her fingers, feeling the ridges still holding cracks of dried paint scrape past her skin, back and forth. “Are you almost done yet?” She drawled lazily.

“There,” I whispered, shaking the can of spray paint after detailing the wall with one last stroke of pink. It made the tinny sound that we’d learned meant it was nearly empty. Satisfied to contemplate the full image for a moment, I leaned back - as far back as I could without falling.

Caitlin and I were kneeling in concrete windowsills, glass long gone. We were confronted with thirty feet of empty air on one side and two shambling floors of rubble on the other, both covered in the litter of hollow paint cans.

For a moment, I stared at the wall directly across from our perch: Childhood nicknames in globular bubble letters and a rainbow wash of neon, two hours in the making: Cat. Emmy. And the bitter smell of aerosol.

I was surrounded by broken pieces and open ends, but for the first time in weeks, my head stopped spinning.

We all need an escape.

“There,” I whispered, shaking the can of spray paint after detailing the wall with one last stroke of pink. It made the tinny sound that we’d learned meant it was nearly empty. Satisfied to contemplate the full image for a moment, I leaned back - as far back as I could without falling.

Caitlin and I were kneeling in concrete windowsills, glass long gone. We were confronted with thirty feet of empty air on one side and two shambling floors of rubble on the other, both covered in the litter of hollow paint cans.

For a moment, I stared at the wall directly across from our perch: Childhood nicknames in globular bubble letters and a rainbow wash of neon, two hours in the making: Cat. Emmy. And the bitter smell of aerosol.

I was surrounded by broken pieces and open ends, but for the first time in weeks, my head stopped spinning.

We all need an escape.

For some people, it’s an island. It’s a mountain, it’s a forest. It’s somewhere clean, serene, and beautiful. But we don’t want that. We come from money, we come from illusions of perfection. We come from snowglobe cities with synthetic smiles and postcard parkways. For us, the escape is somewhere dirty, somewhere old, somewhere secret. It makes us uncomfortable, stumbling over rubble. It makes us scared, possibly being followed. It makes us exhilarated, finally doing the wrong thing.

Nobody wants to be perfect all the time.

“Imagine if they found us,” Caitlin whispered, glancing down at the abandoned warehouse floor and then back up to where we sat, legs hanging from window sills on the shaky second level. “I wonder if they’d climb all the way up here... you know, just to get us in trouble.”

She was smiling, but she turned her head toward the open side of the window so that I wouldn’t see completely. She’d like to see them try, wouldn’t she? Feeling like a renegade was the reason we ran away. If only for an afternoon, our polished images were scuffed and tarnished.

Everybody likes to feel like a rebel, sometimes.

We were only feet away from likely death, sitting in our windows, but I had never felt more alive. Staring out across the expanse of the city from an unknown lookout, the world seemed so small. It felt like it was ours, and we were the only ones who could see it, at least in this way. That building - that ancient ode to Milwaukee’s trademark Cream City brick - that was our canvas. That wall - with its rainbow-tinted new mural of angular shapes and smudged lines - that was our artwork. And we were vandals.

“If they find us, they can’t catch us,” I said. My voice was only a quiet echo in the forgotten factory, but there was a confidence to the words.

Everyone wants to think they’re badass.

Nobody wants to be perfect all the time.

“Imagine if they found us,” Caitlin whispered, glancing down at the abandoned warehouse floor and then back up to where we sat, legs hanging from window sills on the shaky second level. “I wonder if they’d climb all the way up here... you know, just to get us in trouble.”

She was smiling, but she turned her head toward the open side of the window so that I wouldn’t see completely. She’d like to see them try, wouldn’t she? Feeling like a renegade was the reason we ran away. If only for an afternoon, our polished images were scuffed and tarnished.

Everybody likes to feel like a rebel, sometimes.

We were only feet away from likely death, sitting in our windows, but I had never felt more alive. Staring out across the expanse of the city from an unknown lookout, the world seemed so small. It felt like it was ours, and we were the only ones who could see it, at least in this way. That building - that ancient ode to Milwaukee’s trademark Cream City brick - that was our canvas. That wall - with its rainbow-tinted new mural of angular shapes and smudged lines - that was our artwork. And we were vandals.

“If they find us, they can’t catch us,” I said. My voice was only a quiet echo in the forgotten factory, but there was a confidence to the words.

Everyone wants to think they’re badass.

But you can’t be, not always. Because that’s exactly when we heard the scuffle, saw the black-capped head enter through the loose board in the wall we thought only we knew as a secret door. That was the moment we froze in place, hoping he’d look past us, but he was already shouting to his group that he wasn’t alone.

Sometimes, coming from a privileged world gives you this complex of invincibility, but the two police officers that dashed into the building didn’t see our sky-high GPAs and three-story houses as their boots broke through the debris. You realize pretty quickly how much danger you are in, especially when a third man runs in with a ladder and leans it against the machines you had used to climb up. Trapped.

We’re all in love with the action, but we don’t want the consequences.

And then they were on top of us. Flashlight beams cutting across our skin like lasers. Walkie-talkies spitting static. Footsteps crashing through the piles of wood with no regard for the way decay had balanced them so artistically. Closer, closer. Voices echoing across the empty space, and it wasn’t quiet anymore.

“Down the pipe!” Caitlin screamed, snatching my hand.

I grabbed the metal pole and slid like a firefighter without giving myself time to think. The minute my feet hit the ground, I bolted toward the narrow opening. Caitlin was only two steps behind when our feet hit the grass outside the building, daring the police to race us out. Even though I knew there was a heavy fine resting on our escape, I could feel a smile fighting to pry itself onto my face. Looking back at Caitlin with adrenaline pulsing through my veins, I saw the climax unfolding for a story we couldn’t wait to tell. It would be a thriller, for sure, but that wasn’t why we did this.

Sometimes, the high just comes from breaking the law.

Sometimes, coming from a privileged world gives you this complex of invincibility, but the two police officers that dashed into the building didn’t see our sky-high GPAs and three-story houses as their boots broke through the debris. You realize pretty quickly how much danger you are in, especially when a third man runs in with a ladder and leans it against the machines you had used to climb up. Trapped.

We’re all in love with the action, but we don’t want the consequences.

And then they were on top of us. Flashlight beams cutting across our skin like lasers. Walkie-talkies spitting static. Footsteps crashing through the piles of wood with no regard for the way decay had balanced them so artistically. Closer, closer. Voices echoing across the empty space, and it wasn’t quiet anymore.

“Down the pipe!” Caitlin screamed, snatching my hand.

I grabbed the metal pole and slid like a firefighter without giving myself time to think. The minute my feet hit the ground, I bolted toward the narrow opening. Caitlin was only two steps behind when our feet hit the grass outside the building, daring the police to race us out. Even though I knew there was a heavy fine resting on our escape, I could feel a smile fighting to pry itself onto my face. Looking back at Caitlin with adrenaline pulsing through my veins, I saw the climax unfolding for a story we couldn’t wait to tell. It would be a thriller, for sure, but that wasn’t why we did this.

Sometimes, the high just comes from breaking the law.

HOW WILL YOU GET YOUR SHOES DIRTY?

#whiteconverseproject

In 2015, I got a pair of white converse for Christmas. I hated them.

It wasn't for the right reasons either. I thought white converse were basic. I wanted to be unique, and I wanted to be adventurous. But it was from these shoes that this entire website was born.

I went to the Missile Launch site one time and took the photo shown below. I liked it so much that I started taking them everywhere, and I pushed myself to bring my shoes to as many places as I could that I wasn't supposed to be. Sometimes I brought friends, sometimes friends brought me. I was determined to turn them black by the end of the summer, before I went to college. Ask my how my shoes look now. I dare you. All I'm saying is that I don't call them my "white converse" anymore - no one would believe me.

It wasn't for the right reasons either. I thought white converse were basic. I wanted to be unique, and I wanted to be adventurous. But it was from these shoes that this entire website was born.

I went to the Missile Launch site one time and took the photo shown below. I liked it so much that I started taking them everywhere, and I pushed myself to bring my shoes to as many places as I could that I wasn't supposed to be. Sometimes I brought friends, sometimes friends brought me. I was determined to turn them black by the end of the summer, before I went to college. Ask my how my shoes look now. I dare you. All I'm saying is that I don't call them my "white converse" anymore - no one would believe me.

ROADS TO NOWHERE originally published for North by Northwestern, 11/16/2016 |

There are so many times a day when someone asks you where you’re going.

Maybe you’re on the Metra, and the conductor wants to know where you’re getting off. You’re walking down Sheridan; your friends want to know when to meet you at the library later. You’re meeting with your adviser; she wants to know what you want to do next quarter, or after graduating, or with your life.

We’re supposed to have answers. We’re expected to make goals, to pursue them, and be constantly aware of our proximity to attainment on the road to success. As much as I aspire to go somewhere in life, these questions are exactly what I run away from. Sometimes, I just want to take a road without knowing where it will take me. Sometimes, it’s not even a road.

People see me running sometimes and they’ll ask what I am running toward. If they’re insightful, they might even ask what I’m running from. I guess it doesn’t occur to people that I could just be running for the sake of running.

Other runners understand this feeling better than anyone. My team back home would set off on a run without really choosing a direction. Most of the time, we didn’t find anything particularly interesting, but every so often we’d stumble across a gem. One time it was a dark tunnel that took us underneath the train tracks. One time it was a hidden treehouse, complete with two levels and a rope-and-pulley system. One time it was a quarry we hadn’t heard of, tucked in the dense woods behind the local church. On each of those occasions, we stopped our watches and took time to explore, running through the tunnel, climbing into the treehouse, splashing each other in the quarry. Each time, I remember laughing and messing around the way you do when you don’t have phones to capture the moment; instead simply trying to take everything in for the sheer sake of collecting memories like stamps. Every time I ruined a pair of shoes or ripped a cotton t-shirt, I decided it was ultimately worth it. Looking back on the stories behind each snare, all I can think is, we were kids. We were all such kids.

The same thought crossed my mind this past weekend. I rented bikes with a few of my friends and we went straight north until the sun set, air whistling through the spokes of our tires and blowing pieces loose from our hair. On the way back, I spontaneously swerved into an alley between houses and we all ended up in the parking lot of an elementary school with a basketball court and a miniature track.

“How long do you think it’ll take me to get all the way around this?” One of my friends asked, hands pulsing on the handles as if it was a motorcycle instead of a Divvy bike.

We took turns timing each other, laughing as we ripped around the tiny track, crossing through lanes and cheating by cutting through the middle. In the fading light from the setting sun, ponytail bouncing with each leap, I found myself trampling across the parking lot of an elementary school with three other students and again thought about how juvenile I felt.

The whole ride home, we reminisced about how much fun we were having until I finally realized the appeal. It wasn’t acting like a kid that I enjoyed; it was the sheer absence of a plan. I missed snaking through neighborhoods and rolling down unknown streets, checking over my shoulder to make sure my friends had followed, but most of all, I missed exploring. I missed riding without a purpose, then finding it along the way.

It was the same feeling that came from those winding childhood road trips, drives where we pulled to the side of the road whenever we saw something interesting, until the destination wasn’t nearly as important as the stops we made along the way. Often, I think back on journeys from the backseat and wonder why I only remember parts of the trip. Why is it that I can’t say where we were going? I guess it was never important.

Maybe that’s the reason I go on runs, bike rides, and road trips. Maybe I don’t like starting out with a destination in mind; maybe I know it doesn’t matter. Maybe I understand that the second you win the race, you’ve lost the moment. Maybe I know that by the time you reach the end of the road trip, the journey is over.

My favorite place to go is nowhere.

Maybe you’re on the Metra, and the conductor wants to know where you’re getting off. You’re walking down Sheridan; your friends want to know when to meet you at the library later. You’re meeting with your adviser; she wants to know what you want to do next quarter, or after graduating, or with your life.

We’re supposed to have answers. We’re expected to make goals, to pursue them, and be constantly aware of our proximity to attainment on the road to success. As much as I aspire to go somewhere in life, these questions are exactly what I run away from. Sometimes, I just want to take a road without knowing where it will take me. Sometimes, it’s not even a road.

People see me running sometimes and they’ll ask what I am running toward. If they’re insightful, they might even ask what I’m running from. I guess it doesn’t occur to people that I could just be running for the sake of running.

Other runners understand this feeling better than anyone. My team back home would set off on a run without really choosing a direction. Most of the time, we didn’t find anything particularly interesting, but every so often we’d stumble across a gem. One time it was a dark tunnel that took us underneath the train tracks. One time it was a hidden treehouse, complete with two levels and a rope-and-pulley system. One time it was a quarry we hadn’t heard of, tucked in the dense woods behind the local church. On each of those occasions, we stopped our watches and took time to explore, running through the tunnel, climbing into the treehouse, splashing each other in the quarry. Each time, I remember laughing and messing around the way you do when you don’t have phones to capture the moment; instead simply trying to take everything in for the sheer sake of collecting memories like stamps. Every time I ruined a pair of shoes or ripped a cotton t-shirt, I decided it was ultimately worth it. Looking back on the stories behind each snare, all I can think is, we were kids. We were all such kids.

The same thought crossed my mind this past weekend. I rented bikes with a few of my friends and we went straight north until the sun set, air whistling through the spokes of our tires and blowing pieces loose from our hair. On the way back, I spontaneously swerved into an alley between houses and we all ended up in the parking lot of an elementary school with a basketball court and a miniature track.

“How long do you think it’ll take me to get all the way around this?” One of my friends asked, hands pulsing on the handles as if it was a motorcycle instead of a Divvy bike.

We took turns timing each other, laughing as we ripped around the tiny track, crossing through lanes and cheating by cutting through the middle. In the fading light from the setting sun, ponytail bouncing with each leap, I found myself trampling across the parking lot of an elementary school with three other students and again thought about how juvenile I felt.

The whole ride home, we reminisced about how much fun we were having until I finally realized the appeal. It wasn’t acting like a kid that I enjoyed; it was the sheer absence of a plan. I missed snaking through neighborhoods and rolling down unknown streets, checking over my shoulder to make sure my friends had followed, but most of all, I missed exploring. I missed riding without a purpose, then finding it along the way.

It was the same feeling that came from those winding childhood road trips, drives where we pulled to the side of the road whenever we saw something interesting, until the destination wasn’t nearly as important as the stops we made along the way. Often, I think back on journeys from the backseat and wonder why I only remember parts of the trip. Why is it that I can’t say where we were going? I guess it was never important.

Maybe that’s the reason I go on runs, bike rides, and road trips. Maybe I don’t like starting out with a destination in mind; maybe I know it doesn’t matter. Maybe I understand that the second you win the race, you’ve lost the moment. Maybe I know that by the time you reach the end of the road trip, the journey is over.

My favorite place to go is nowhere.